From ancient Egypt to the Hindu kingdoms of India and Indigenous America, the Seshat History of Moralizing Religion examines how religious systems evolved—and what they reveal about humanity

[Vienna, July 21, 2025] –The book Seshat History of Moralizing Religion explores how societies across the world have answered some of the oldest human questions: What do the gods want from us? Will we be judged after death? What is the purpose of religion and ritual?

Every major religion today recognizes interpersonal morality as a primary concern, reinforced by supernatural punishment and reward—the belief that gods or cosmic forces reward good behavior and punish wrongdoing. In the Abrahamic faiths, an all-powerful god monitors and judges human conduct, and in Asian karmic religions, every action has consequences, in this life or the next.

However, moralizing supernatural punishment and reward in non-Abrahamic religions have rarely been studied in depth, particularly in terms of their historical development and their role in human societies, point out the editors of this book, published by Beresta Books later this month.

“This book is a large-scale comparative project marshalling evidence for religious change in historical context across a wide range of societies from the Neolithic to the present day, and is a novel contribution to our understanding of religion,” says Jenny Reddish, one of the editors along with Peter Turchin and Jennifer Larson.

Global and Detailed Look

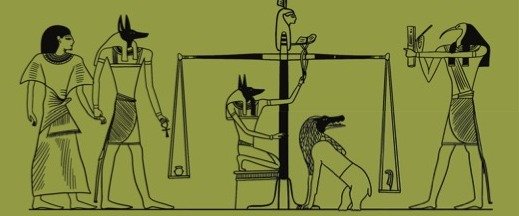

“What sets this book apart is its global scope,” adds Turchin. “The real surprise came in the details—how different societies developed unique ideas about moralizing supernatural punishment and reward. From ancient Egypt’s concept of ma’at to the Indo-European traditions, Hawaiian state gods, and Aztec beliefs about the afterlife for warriors, the diversity is fascinating. Even systems like karma, which don’t involve gods at all, challenge how we think about morality and the supernatural,” points out Turchin, who leads the Complexity Science Hub’s (CSH) research group on Social Complexity and Collapse.

The book draws on over a decade of global historical research, collected and compiled in Seshat: Global History Databank, and offers a collection of essays by leading archaeologists, historians, and anthropologists. Covering over 30 world regions, the book offers a broad yet nuanced account of religious evolution and its implications for understanding social and moral development.

Early Adopters

Throughout the book, surprising insights are revealed about the development of religious traditions with a strong moral agenda. “Egypt stands out as an early rider in the evolution of moralizing religion,” states Reddish, a scientist at CSH and lead editor of the Seshat Databank.

“Starting in Egypt’s Old Kingdom period (around 2575–2150 BCE), writings such as tomb inscriptions began to mention the idea of divine punishment and reward, along with ma’at—the principle of cosmic justice and harmony”, explains Reddish.

“By the time of the New Kingdom (around 1540–1070 BCE), Egyptians had developed an elaborate set of beliefs about judgment after death and the fate of the soul in the next world. In other parts of Eurasia, similar religious ideas didn’t appear until much later, during what scholars call the Axial Age (around 800–200 BCE).”

Oaths and Treaties

More generally, it was striking how often oaths and treaties overseen by gods were mentioned in the accounts of religious development in different societies, according to Reddish. This was the case for both “moralizing religions” and those in which moralizing supernatural punishment and reward were not central, such as many Indo-European polytheisms, such as Norse, Greek, and Indo-Iranian.

“We still use oaths today, but they are vestigial compared to their comprehensive use in every aspect of public Greek life, such as mercantile, judicial, political, and athletic. It shows how initially self-regarding gods could be ‘harnessed’ in the cause of enforcing interpersonal morality,” adds Larson, a professor at Kent State University.

Prayers and Penance

The book also includes several chapters that examine how the concepts of moralizing punishment and reward have operated within doctrinal religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Manichaeism, and Islam. These chapters emphasize the internal diversity and evolution of these traditions over time.

Tamás Biró of Eötvös Loránd University observes that the notion of punishment and reward after death gained greater prominence in Rabbinical Judaism, after 70 CE, than it had in earlier periods. The chapters also show that the threat of divine punishment is not the sole mechanism by which moralizing religions have encouraged ethical conduct, built large followings, and sustained themselves. Equally significant are shared rituals and institutional structures—for example, annual martyr festivals in Manichaeism, daily prayers in Islam, and the veneration of bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism.

The Case of the Americas

Archaeologist R. Alan Covey took a fresh look at colonial-era writings about Indigenous American religions, pointing out that these accounts were often biased and aimed at making the shift to Christianity seem easier. In the book, Covey concludes that the extent of belief in moralizing gods and supernatural punishment in the Americas has likely been overstated.

“Descriptions of contact-era complex societies indicate that [beliefs in moralizing supernatural punishment and reward] were absent or not well developed, suggesting that such beliefs did not coevolve with sociopolitical complexity in the precontact Americas,” writes Covey, from the University of Texas at Austin.

Complex Societies and Moralizing Gods

“We decided to study the concept of moralizing supernatural punishment and reward across cultures because it's believed to have played a key role in helping societies grow larger and more complex,” explains Reddish.

As explored in books like Big Gods by Ara Norenzayan and God Is Watching You by Dominic Johnson, the idea is that belief in supernatural forces that reward good behavior and punish bad conduct may have helped people cooperate and build stable communities. “Our goal was to better understand what drives cultural evolution over time, using a mix of expert knowledge and data analysis,” adds Reddish.

“We found that beliefs in punitive, omniscient gods or forces cannot explain the initial emergence of social complexity in deep prehistory. However, once fully moralizing religions developed in the last millennium BCE, they had remarkable sticking power and dynamism, and played a key role in imperial expansion and statecraft.”

This book builds on earlier work by Peter Turchin and his team, including a paper that found moralizing gods often appeared after—not before—societies had already become large and complex.

Book Details

Title: The Seshat History of Moralizing Religion

Editors: Jennifer Larson, Jenny Reddish & Peter Turchin

Publisher: Beresta Books

Publication Date: July 2025

Format: Paperback / eBook

ISBNs: Volume One: 978-1-967343-00-3 / 978-1-967343-01-0 // Volume Two: 978-1-967343-02-7 / 978-1-967343-03-4

About the Seshat Project

The Seshat: Global History Databank is an interdisciplinary project that collects and analyzes data about the structure, religion, and culture of past societies to test scientific hypotheses about human history. Established in 2011 by Turchin, Harvey Whitehouse, and Pieter François, it compiles historical knowledge across hundreds of societies worldwide, spanning 10,000 years of human history.

About CSH

The Complexity Science Hub (CSH) is Europe’s research center for the study of complex systems. We derive meaning from data from a range of disciplines – economics, medicine, ecology, and the social sciences – as a basis for actionable solutions for a better world. CSH members are Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT), BOKU University, Central European University (CEU), Graz University of Technology, Interdisciplinary Transformation University Austria (IT:U), Medical University of Vienna, TU Wien, University of Continuing Education Krems, Vetmeduni Vienna, Vienna University of Economics and Business, and Austrian Economic Chambers (WKO).