Belonging to more than one marginalized group can make building and maintaining social connections significantly harder, often in ways that go far beyond a simple sum of disadvantages. A new study shows how inequalities in social ties don’t just add up—they can amplify one another.

[Vienna, November 5, 2025] — Why do some people have more friendships, more support, and more opportunities—while others seem to have far fewer? Is it simply a matter of personal choices, or do structural patterns play a deeper role?

For individuals who belong to a disadvantaged social group, forming connections tends to be more difficult. And for those who belong to multiple such groups, the challenge is even greater. A new study from the Complexity Science Hub (CSH) together with TU Graz, published in Science Advances, reveals that differences in the number of social ties across groups cannot be explained merely by tallying up individual forms of discrimination. “Instead, disadvantages can amplify one another when they intersect,” says study author Samuel Martin-Gutierrez.

To understand how different aspects of identity, such as gender and ethnicity, affect social networks, the researchers developed a mathematical model and tested it using friendship data from around 40,000 U.S. high school students. “Our findings show that tie disadvantages often emerge in unexpected ways when multiple identity traits overlap,” states Fariba Karimi, head of the Algorithmic Fairness research group at CSH and professor at TU Graz.

Birds of a Feather

Social networks don’t form at random. Who we are—our gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic background—influences whom we connect with. We tend to form relationships with those who are similar to us, a phenomenon known as homophily.

On a larger scale, this tendency means that certain groups are more likely to be well-connected both within their communities and to the central, influential parts of the social network. These groups enjoy greater access to social information and mutual support, which can, in turn, condition broader access to opportunities.

Marginalized groups, on the other hand, are pushed to the periphery of the social network. They not only have fewer connections to its central parts but also tend to be connected to others who are themselves less well-connected, making it harder to access opportunities, such as jobs or educational pathways. “When majority groups mostly connect among themselves, it creates a kind of structural invisibility for minorities,” explains Martin-Gutierrez, who conducted the research while at the CSH.

Compounding Disadvantages

But what does this mean for people who belong to more than one marginalized group—such as women with a migrant background from low-income families? “When someone falls into more than one marginalized category, the effects don’t simply add up—they can intensify in nonlinear and sometimes unexpected ways,” says Martin-Gutierrez.

Until now, these so-called intersectional inequalities have been understudied. Much of the existing research has focused on how individual identity traits, such as gender or ethnicity, affect social tie formation. “What sets our study apart is that we show how multiple identity factors can interact to shape social networks,” explains Martin-Gutierrez. “Depending on group size, connection preferences, and correlations between traits, entirely new and complex patterns of advantage and disadvantage can emerge.”

Real-World School Data

To capture these intersectional dynamics, the researchers developed a network model and tested it against real data from over 40,000 U.S. high school students from the years 1994/95. The patterns of tie inequality predicted by the model closely matched the observed friendship patterns, with about 92% accuracy.

The dataset included students’ self-nominated friendships—each student listed who they considered friends, as well as demographic details like gender, ethnicity, and grade level.

The findings clearly demonstrate how overlapping disadvantages can interact: While girls generally had more friends than boys, Black girls were the exception and, together with Asian boys, had among the fewest connections – fewer than Black boys, and far fewer than white girls. In their case, the structural disadvantages of being both Black and female outweighed the broader trend that girls tend to be nominated as friends more often than boys.

White girls, by contrast, had the most social ties. As members of both the ethnic majority and a gender group more likely to receive friendship nominations, they benefited from multiple structural advantages. White boys still gained from being part of the ethnic majority, resulting in higher overall popularity compared to Black boys. “One surprising pattern we observed was that in certain grade levels, Black boys were better connected than others, despite facing two layers of structural disadvantage,” says Martin-Gutierrez. “This is an example of emergent intersectionality: unexpected advantages that arise from complex interactions between group preferences, group sizes, and contextual factors,” adds Karimi.

“These kinds of effects have often remained hidden in earlier studies because they focused on one trait at a time,” Karimi notes. “Our findings underscore how important it is to consider people in their full complexity.” This new method, the researchers say, could help inform the design of schools, social platforms, and policy programs—making it easier to identify and address structural disadvantage early on.

Explore Social Fairness

In this interactive visualization, you can discover what social fairness means—and how it can be influenced.

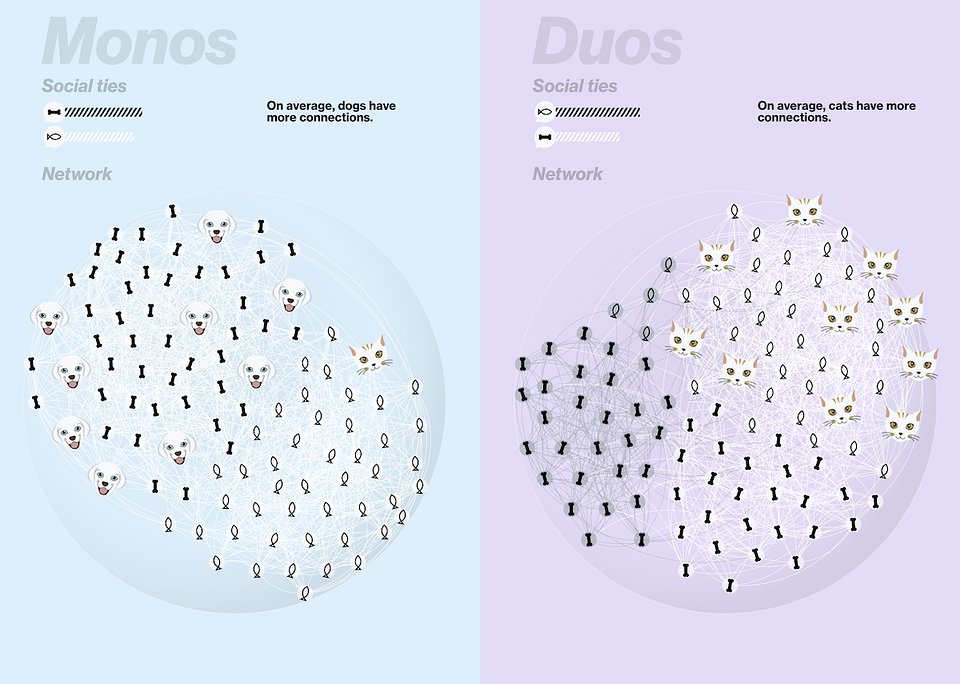

In a fictional parallel universe, there are two planets: Monos and Duos, inhabited by cats and dogs. Each year, the ten most popular residents are ranked based on their social connections.

Playfully explore whether this ranking system is fair. Do certain factors— such as species or color—lead to hidden inequalities that favor some groups over others? You can create your own planet and experiment with these factors to see how they affect the rankings.

About the Study

The study “Intersectional inequalities in social ties,” by Samuel Martin-Gutierrez, Mauritz N. Cartier van Dissel, and Fariba Karimi has been published in Science Advances (doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adu9025)

This work is part of the ERC-funded project NetFair and will help to devise fairness tools for social networks. The study was also supported by the projects MAMMOth (Multi-Attribute, Multimodal Bias Mitigation in AI Systems) funded by Horizon Europe and ESSENCSE funded by the FFG.

About CSH

The Complexity Science Hub (CSH) is Europe’s research center for the study of complex systems. We derive meaning from data from a range of disciplines – economics, medicine, ecology, and the social sciences – as a basis for actionable solutions for a better world. CSH members are Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT), BOKU University, Central European University (CEU), Graz University of Technology, Interdisciplinary Transformation University Austria (IT:U), Medical University of Vienna, TU Wien, University of Continuing Education Krems, Vetmeduni Vienna, Vienna University of Economics and Business, and Austrian Economic Chambers (WKO).